'Virtual Orientalism', a book review

For meditators and Buddhist converts who come from Western, Judeo-Christian backgrounds, encountering the Buddha’s teachings can seem like a thrilling voyage into a foreign land filled with mind-expanding concepts and magical aesthetics. We give ourselves up to practices—both mental and physical—that seem utterly strange to the communities we came from. We often use words like “transformative” or “life-changing” to describe the impact Buddhism has had on our lives.

However, we less frequently consider the changes being wrought in the opposite direction. How do the values and perceptions we bring to the table shape how we understand, describe, and practice the Buddha’s teachings? Even more rarely do we admit to distorting the Buddha’s teachings to fit our ingrained values and cultural preferences to create narratives that reinforce our self-image and further our interests.

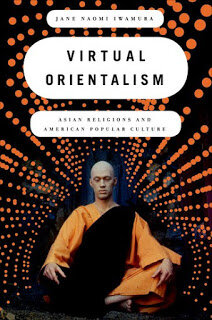

“Virtual Orientalism” (2011) by Jane Naomi Iwamura shines a light on how Westerners have been doing precisely this in the mass media for nearly a century, if not longer. The term “Orientalism,” coined by Edward Said in his eponymous 1978 book, is used to refer to Western depictions of Asian/Eastern life, culture and thought, usually in a patronizing manner, even if it does not superficially appear so. While Orientalism takes many forms—“the inscrutable Oriental, evil Fu Manchus…Dragon Ladies”—Iwamura focuses on a distinctly religious form, what she calls the “Oriental Monk.” Her definition is as follows:

“The term Oriental Monk is…meant to cover a wide range of religious figures (gurus, bhikkhus, sages, swamis, sifus, healers, masters) from a variety of ethnic backgrounds (Japanese, Chinese, Indian, Tibetan). Although the range of individual figures points to a heterogeneous field of encounter, all of them are subjected to a homogeneous representational effect [that blunts] the distinctiveness of particular pers

ons and figures. Indeed, the recognition of any Eastern spiritual guide, real or fictional, is predicated on his conformity to general features…: his spiritual commitment, his calm demeanor, his Asian face, his manner of dress, and—most obviously—his peculiar gendered character.”

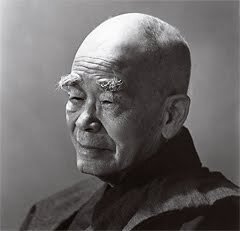

The three figures Iwamura focuses on are the legendary Zen teacher and author D.T. Suzuki, the famed Indian guru Maharishi Mahesh, and the hero Kwai Chang Caine from the TV series “Kung Fu.” In great detail, she guides the reader through depictions of the first two in the contemporary popular press, and describes how the third fits into her conceptual framework. She skillfully shows how writers and photographers tended to fit these men into stereotypical slots, no matter if the depiction was positive or negative. The Oriental Monk is either offering a ground-breaking spiritual paradigm that fills a gaping void in society, or is selling a bill of goods that is at best leading young people astray and at worst bilking them out of their (or their parents’) hard-earned cash. The Oriental Monk is always calm and enigmatic, but this is either a sign of great peace and inner strength, or evidence of an effeminate culture that lacks the dynamism of the West.

Because I was only glancingly familiar with them, the chapters on Maharishi and Caine felt more like academic case studies, interesting but distant. The section on Suzuki, on the other hand, cut closer to the bone. For those who grew up with little exposure to Asian cultures or religions, myself included, indulging in Orientalist tropes is almost unavoidable, particularly in the early stages of the encounter. Iwamura describes the intense focus Suzuki’s external appearance received in the American press. Authors used words such as “ferocious,” “angry demons,” “exotic butterflies” to describe, of all things, his eyebrows. His “eye slits” (is he wearing a mask?) get compared to tadpoles. His clothing also receives unusual treatment. While many photographs of Suzuki had him in traditional Japanese robes, in fact he apparently appeared in public mostly in a sports jacket and slacks. In photos of Suzuki online he does not appear terribly distinctive, or only in the way that all faces are distinctive. It is easy to see that the authors of the day used his face as a canvas upon which to paint their own image of Zen and Asia which he represented. Still I must admit, his eyebrows were quite bushy.

The treatment of a regular Japanese face as an object of extreme exoticism and profound insight reminded me of a realization I had long ago about how many Westerners approach Asian religions. I was raised Protestant. Nothing too religious, nothing too exciting, just a plain, pillar-of-the-community kind of neighborhood church that was long a staple of American life. Though I had a hard time seeing it, I was surrounded by the strange and magical: astounding Biblical tales, bloody Christ on his cross, odd ceremonies involving quasi-cannibalism, decorated evergreens, and painted eggs. Yet to me these were humdrum: that boring book with stories I had heard a thousand times, just another statue of Jesus, and the cozy rituals of Communion, Christmas, and Easter.

When I arrived in Asia, I was understandably awed by its religions: towering gold pagodas in Myanmar, gods of wind and thunder guarding temple gates in Japan, hypnotizing chanting by Tibetan monks. One day, however, I realized I had been seeing everything through the eyes of a foreigner. If I had been born in these societies, I might look at these objects with the familiarity and indifference with which I had seen the trappings of Christianity. To a local, golden pagodas and fire god statues might not receive any more notice than I had given my church’s steeple and stained glass windows. Would the chanting of monks cease to be transcendent and instead sound like a pastor’s droning sermon? And when I had this realization, the whole project—the exploration of Eastern spirituality—seemed absurd, ironic. Here were all these Westerners who were fed up with the superficiality and rigidity of the organized religions of their homeland, running headlong into the arms of organized religions in other lands. It would be one thing if we were all running away from superficiality and rigidity toward depth and tolerance, yet the reality was that Asian organized religions played a very similar role in their home societies: that of conservative bastions of tradition and authority.

Of course, this insight was only a partial truth. Depth and tolerance can be found in Buddhism and other Asian religions (as it can in Western religions), but the more interesting journey comes when one decides to evaluate and compare spiritual traditions on their own terms, not as merely the stale traditions one grew up with versus the shiny new objects one encountered in the exotic East. There are important philosophical and other differences between Buddhism and Christianity, ones that have a profound impact on how one exists in and approaches the world. Deciding to pursue one path and not the other (or neither) is one of the most important forks one will come to in life.

In some ways, I feel this is the journey out of Orientalism. One initially sees the East only heavily overlaid by the conditioning of culture and background, yet with long exposure and sincere exploration, the scales will gradually fall from one’s eyes to reveal, if not ultimate truth, then at least a less biased perception. But similar to what happens in Buddhist practice, there is a danger of mistaking an early insight for the final one. The roots of Orientalism can be deep and insidious, remaining even after the worst of it is removed.

One of my biggest disappointments with Iwamura’s book was that it focused almost exclusively on Orientalist depictions by people with only a superficial understanding of Asian cultures and religions, such as reporters for popular magazines and Hollywood screenwriters. This is not a fault of the book, since these are the author’s stated subjects. Still, she does mention a few Westerners who are serious students, including Gary Snyder and Alan Watts in the section on Zen, and she makes a number of brief statements of dazzling perceptivity that are unfortunately not followed up on. One such quote is, “[T]he particular way in which Americans write themselves into [Oriental Monk narratives] is not a benign, nonideological act; rather, it constructs a modernized cultural patriarchy in which Anglo-Americans reimagine themselves as the protectors, innovators, and guardians of Asian religions and culture and wrest the authority to define these traditions from others.” This sentence landed in my gut like a heavy book hitting a table. I have never intentionally supported a “cultural patriarchy” or consciously done anything to “wrest the authority” away from anyone. Still, I felt these words applied in some sense to attitudes I have harbored and maybe still do. Indeed, my praise of “The Broken Buddha” in a previous post could easily be interpreted as cheerleading for yet another Anglo-American reimagining himself as a protector, innovator, and guardian, this time of Theravada Buddhism.

Another quote describes David Carradine’s attitude toward playing a Shaolin monk on TV. Even though the actor admits he “couldn’t get interested in Eastern mysticism or any of those things,” he expresses a desire to portray the character in a “pure” way. Iwamura notes, “The ideal of which Carradine speaks seemed to rely on conveying an authenticity based on his own beliefs and values. Kwai Chang Caine and his Shaolin background became a convenient vehicle through which this ideal could be achieved.” This very concisely describes a dilemma Westerners walk right into when getting involved in Buddhism. Many of us are dissatisfied with the values and practices of the societies we grew up in, and have vague notions of finding replacements that are somehow more fulfilling and meaningful. Buddhism provides an avenue that checks many of the boxes we seek: instead of empty materialism it offers satisfaction with simplicity, instead of mindless efficiency and frenetic activity it values contemplation and stillness, instead of slavish adherence to tradition it encourages you to know yourself. These are important concerns, and the Buddha’s teachings provide a path for resolving them. However, there is much more to Buddhism, some of which challenges the values that many Westerners bring to the table. If one simply keeps to the values one arrived with and dismisses everything that does not align as backward superstition or archaic tradition, what was the meaning in adopting a foreign religion in the first place? One might as well have just remained a counterculture Westerner. At very least, Carradine can be praised for not engaging in this type of disingenuousness.

The combination of the above two attitudes—an inflated sense that one knows Buddhism’s “true essence” and the facile dressing of one’s own values in a Buddhist costume—is particularly pernicious. This tends to manifest as an archetype the West had been exporting since Columbus: the arrogant foreigner who thinks he or she knows better than the benighted natives. And I certainly do not want to be that guy. Yet, and this is another area Iwamura does not address, there also needs to be space for legitimate critiques of how Buddhism is actually being practiced and for honest exploration of which values should be kept and which should be jettisoned. Dismissing the critiques of Theravada in “The Broken Buddha” as mere Orientalism would be foolish, though making or discussing these critiques without an understanding of the sordid history of Orientalism is just looking for trouble.

Overall Iwamura is a good writer and the book moves along at a good pace, helped by its brevity at less than 170 pages. The biggest drawbacks in my view were a tendency to lapse into stultifying and sometimes virtually meaningless academia-speak and a habit of stating what felt like subjective opinions as objective fact. Thankfully both of these occur infrequently enough so as not to ruin the book. A text about how Orientalism manifests among serious students of Buddhism would have been more pertinent to my own journey, but even with her focus on pop culture depictions and non-Buddhist figures, Iwamura’s book helped tear another rent in the veil.